Get Ready to Drift: GOES-17 Begins Move to Its New Operational Position

October 22, 2018

This article was updated on October 23, 2018, to revise the details of the GOES-15 drift.

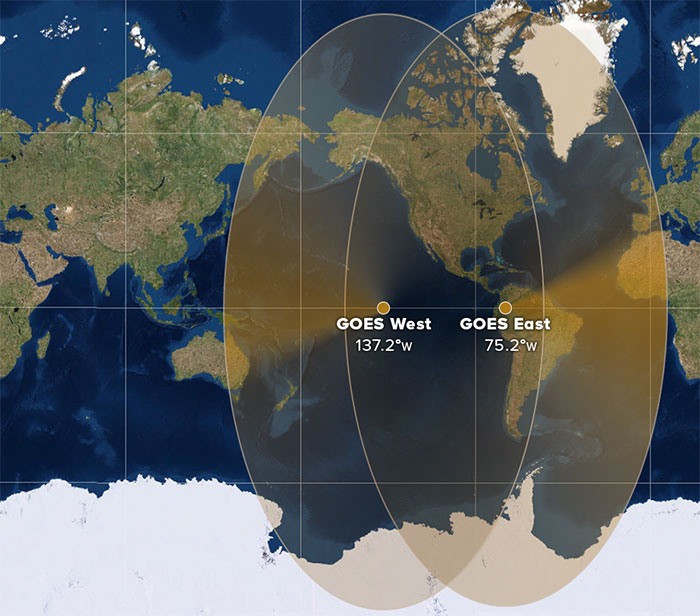

NOAA’s GOES-17 satellite is getting ready to move to its new vantage point at 137.2 degrees west longitude, allowing us to see the weather at high resolution in the western U.S., Alaska and Hawaii, and much of the Pacific Ocean.

On a warm, sunny evening in Cape Canaveral, Florida, NOAA launched its newest geostationary satellite, GOES-S, into space from NASA’s Kennedy Space Center. Eleven days after the March 1, 2018 launch, GOES-S reached its geostationary orbit 22,240 miles from Earth and officially became GOES-17. For the past seven months, the satellite has been in a temporary position – at 89.5 degrees west longitude – known as its on-orbit checkout location. Since then, scientists have been testing and calibrating GOES-17’s instruments so it is ready for “prime time” when the satellite becomes operational.

But before that happens, GOES-17 first has to move to its new orbital position over Earth’s equator at 137.2 degrees west longitude. This relocation process, known as “drift,” will take about three weeks to complete.

What happens during drift?

On October 24, at 1:40 p.m. EDT, GOES-17 will begin moving westward – at a rate of 2.5 degrees longitude per day – until it reaches its new position on November 13.

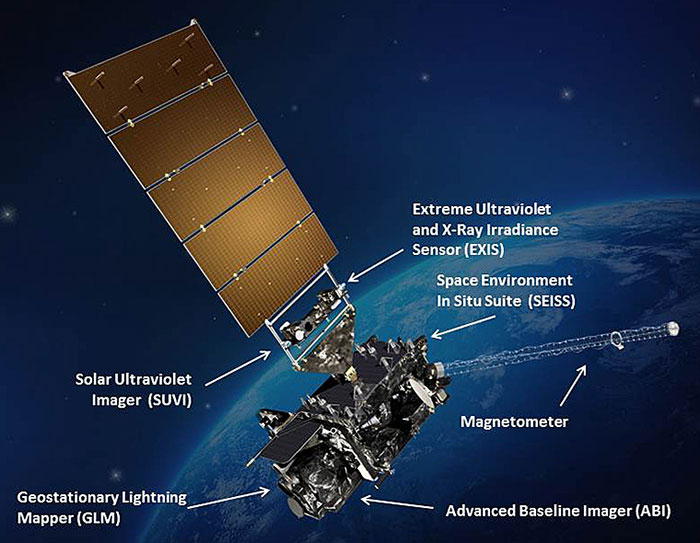

During the drift period, five of GOES-17’s instruments (ABI, GLM, SUVI, SEISS and EXIS) will not be collecting or sending us any data. These are the high-tech sensors we use to see clouds at high resolution, map lightning flashes, or monitor solar flares from space. Other features, including the Search and Rescue Satellite-Aided Tracking (SARSAT) system will also be disabled.

How exactly do these satellites physically get moved from point A to point B thousands of miles above Earth? NOAA's Office of Satellite Product and Operations team can plan all of these maneuvers using navigation software. For a satellite to change its orbital position, it follows a series of commands uploaded by the operations team to the spacecraft's memory. The mission operations center validates and rehearses these maneuver sequences on the ground using a satellite simulator.

Normally, satellites maintain the same distance from Earth while operational and transmitting data. During drift, however, GOES-17's altitude will actually be raised slightly (by about 125 miles). This maneuver helps nudge the satellite to begin moving into its new orbital position. After GOES-17 finishes drifting, NOAA's mission operations team will lower the satellite back to its normal operating altitude. This raising and lowering process is used any time a geosynchronous satellite needs to change orbital positions.

When GOES-17 reaches 137.2 degrees west on November 13, the satellite’s instruments won’t be turned on right away. First, a team of scientists will have to calibrate the instruments to ensure everything is working properly. If everything checks out, the transmitters aboard the spacecraft will be turned back on.

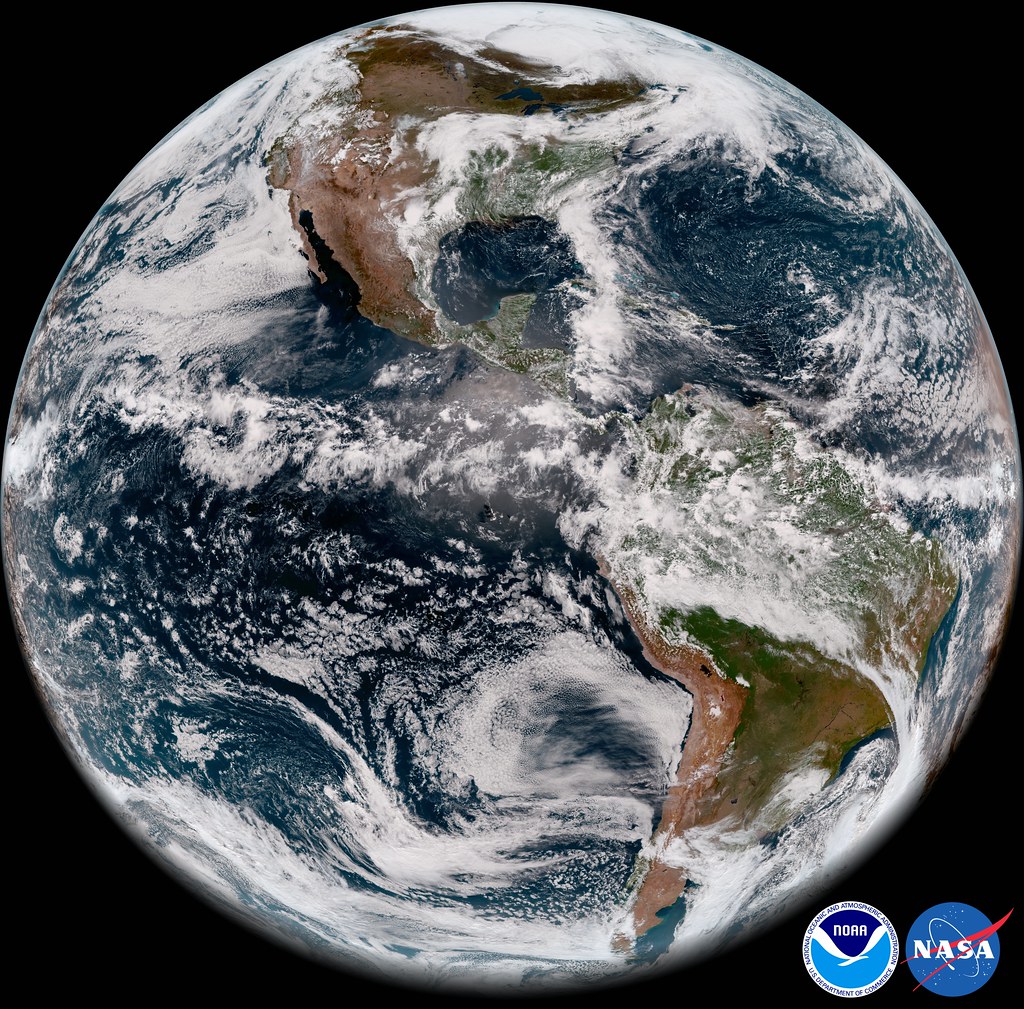

The next big milestone comes November 15, 2018. That’s when GOES-17 will start sending imagery and data via the GOES Rebroadcast System, and we’ll start seeing the first views of Alaska, Hawaii and the Pacific Ocean from GOES-17’s new orbital position. It will be an exciting day for all of us satellite enthusiasts, but the satellite won’t officially be operational just yet. First, GOES-17 will undergo three more weeks of testing to make sure it’s ready for “prime time.” If everything is working properly, GOES-17 will go into operations as NOAA’s GOES West satellite on December 10, 2018.

GOES-17 will considerably improve weather forecasting capabilities across the western United States, particularly in Alaska. “With GOES-17, we will have unprecedented coverage of Alaska from geostationary orbit. The GOES-17 imager has four times the resolution of the previous GOES imager, which will make a substantial difference in northern latitudes,” said Dan Lindsey, senior scientific advisor to the GOES-R Series Program. “GOES-17 is going to provide significant benefit for monitoring hazards often experienced in Alaska such as wildfires, volcanic ash, snow and sea ice.”

As the sister satellite to GOES-16, located in the GOES East position, GOES-17 will extend high-resolution satellite coverage from the west coast of Africa across much of the Pacific Ocean.

The GOES-15 drift

Shortly after GOES-17 starts to drift, NOAA’s current GOES West satellite, GOES-15, will also move to a new orbital home in order to “make room” for the newcomer. Currently, GOES-15 is keeping watch over the Western U.S. and the Pacific Ocean from 135 degrees west longitude. On October 29, GOES-15 will start its own orbital relocation. This is a delay from October 23 due to a National Weather Service Critical Weather Day declaration. A Critical Weather Day is triggered by significant weather or events affecting the United States or its inhabited territories. While GOES-17 will move west, GOES-15 will be moving east at a rate of 0.88 degrees longitude per day until it reaches its new orbital position at 128 degrees west.

Because it won’t need to move as far as GOES-17, the GOES-15 drift will only take nine days to complete. The latter satellite will reach its new orbital position on November 7. Unlike GOES-17, all of GOES-15’s instruments will remain on during the drift.

Tandem operations

Although GOES-15 will hand its “GOES West” title to GOES-17 in mid-December 2018, the former satellite won’t fade into sunset right away. Due to the technical issues with GOES-17’s Advanced Baseline Imager (or ABI, the satellite’s primary instrument), NOAA plans to operate GOES-15 and GOES-17 in tandem for at least six months. This will allow scientists to see how well GOES-17 is working as the new GOES West operational satellite.

While GOES-17 will experience data outages from some of its infrared channels overnight during the warmest parts of the year (before and after the vernal and autumnal equinox, when the instrument absorbs the highest amount of solar radiation), a team of experts has made excellent progress optimizing the performance of the instrument through operational changes. “The GOES-17 ABI is now projected to deliver more than 97 percent of the data it was designed to provide, a remarkable recovery,” said Pam Sullivan, System Program Director for the GOES-R Series Program. “We are confident the GOES constellation will continue to meet the needs of forecasters across the country.”

Looking ahead, NOAA is also implementing changes to the ABI on its future geostationary satellites, GOES-T and GOES-U, to reduce the risk of cooling system anomalies that were seen in GOES-17. The instrument radiator is being redesigned to improve its reliability. Due to this redesign, the planned launch of GOES-T in mid-2020 will be delayed. Once the new ABI radiator design is approved, NOAA will determine a new launch readiness date.

But before then, atmospheric scientists and weather enthusiasts can look forward to GOES-17’s next-generation imagery of developing storms, wildfires, and other environmental phenomena in Alaska, Hawaii, and much of the Pacific Ocean extending all the way to New Zealand. We’ll start seeing these views shortly after GOES-17 completes the journey to its new orbital position at 137.2 degrees west – the future home of NOAA’s new GOES West satellite.

For detailed information about the drift, see the GOES-17 transition to operations webpage.